|

Most of the time, we take so-called classical music, like the music of Bach, at face value, and play the notes and rhythms as they were written down. (Which is somewhat weird, when you think about it, since we don't even play Bach on the instrument it was written for most of the time!) In this post and accompanying video, I’ll show you some of the basic principles I use in changing Bach’s music, in particular the rhythm, and how this process opens up this vast new landscape of musical possibilities for exploration, this vast landscape, that, once you see it, you start to see and hear rhythm a little differently in all the music you hear. Get ready to think about rhythm differently! For me, the end result is not only more musically satisfying for our modern ears that are more attuned to complex rhythms and syncopation from pop and dance music, but also more suited to the piano in particular, since Bach didn’t write music for the piano, per se. As we’ll see this process has a lot to teach us about rhythm and about articulation, and these are just really important things to understand not only in Bach’s music, but in any music, whether you’re a composer, a performer, or just an interested listener. I’m going to use the example of the C minor prelude from the WTC, book 1 as an example. Here's the first two measures.

You can listen to each example in this post by pressing the "play" button in the upper left. If that mechanical sound is grating though (and I know it is), I invite you to listen to my recording of this prelude "as written" on my album Post | Bach. And don't worry, there's a fully syncopated version coming at the end of the post. On one level, the rhythm is very simple, it’s just a constant stream of equally spaced notes: Importantly, though, we have to think of music always in different layers; now this process can get unwieldy, so we’re not going to go too deep into it, but let's start by organizing the music into beats, which you naturally did when you were listening, whether you were aware of it or not. The music is organized so that four notes occur per beat, and there are four beats in each measure. The four beats alternate feeling strong and weak, for reasons that are explained in more detail here. To really understand the beat, though, you have to think about it on several different levels at once, each level alternating strong and weak: The parentheses show notes that "already" happen in a higher level of the hierarchy. Perhaps a little bit easier to see this way: Okay, let's set aside the beats for one moment and think about another way to break the music into layers, that is, into voices. Let's imagine we have four singers singing this piece (the examples play with slightly less ridiculous sounding string instruments). Can you hear that the soprano and bass singers parts have more natural emphasis than the tenor and alto? (Or, at least, they would if the players were not mechanical.) The bass and soprano have some level of primacy over the inner voices in this case. Now we get to our first interesting observation! Can you see that the soprano and bass voices match up or align with the the top two levels of the beat hierarchy (the strong beats)? Can you see that the inner voices, alto and tenor, align with or match up with the two lower levels of the beat hierarchy? The way this music was written, there is a close association between the notes’ strength or emphasis by virtue of where they are in different layers of abstraction, the beat (metric) layer, and the voice layer, one that has metric emphasis and the other that has melodic and rhythmic emphasis. This point is almost so obvious when listening to the music that it is easily overlooked, glossed over, or deemed unimportant. But it is very important to realize! This alignment is common in music; it is, in many ways, the natural order of things. Strong beats attract moments of natural musical emphasis, that is in one sense why they are strong beats, after all. But what happens if we purposely move certain moments of emphasis so that they no longer fall on the strong beats, or stronger moments of the metrical emphasis? This misalignment is what we generally call syncopation. Listen carefully and see if you can hear which beat “moved.”

Did you feel the slight “surprise” anticipation of the third beat, almost like it came too soon? How does that look in our hierarchy? Well, we moved the rhythmic and melodic emphasis of the soprano and bass voices before the beat. If we operate strategically, we can create a strong desire for the emphasis to “return” to the beat, which is a fancy way of saying we can make something that sounds cool. So we’ve made our first syncopation by moving the emphasis before the third beat, but truly we’re just getting started. Let’s try that syncopation a slightly different way.

Did you notice the difference? Now we’ve created a difference not only at the level of the emphasis, but at our first level, that of the basic surface rhythm, which now looks like this: Let’s try that technique now on a different beat other than the third. And now on a different beat: What if we start combining different syncopations on different beats? How about another one? Can we syncopate at the half-beat level of the hierarchy instead of the beat level? (Yes.) Can you see, can you glimpse the vast world of possibilities we’ve unlocked, simply by thinking about the rhythm slightly differently? And we’re still on the first two measures of one single piece! Think about how we can start to change the syncopations as we go through the piece. The possibilities are (for all practical purposes) endless. Here is one amongst those endless possibilities. Compare with the original. What do you think?

0 Comments

This post is a follow-up part 1 here, in which I laid out a musical theme and the different possible rhythmic combinations one could make by "choosing" different "empty" beats. To recap, here's the musical theme, which you can play back by hitting the play button in the upper left corner, along with all examples embedded in this post! (Although warning, they load pretty slowly, it seems.)

Since it has 9 notes over 12 beats, we can vary the rhythm by changing which 3 beats will be without a note, which is equivalent to choosing which 9 beats will have a note. Therefore there are "12 choose 9" or "12 choose 3," or 220, possible rhythmic variations for the theme. At the end of the post, I claimed that 191 of those possibilities are syncopated. So what does it mean for a melody to be syncopated, how did I arrive at that number, and why does it matter that there are so many more syncopated possibilities than non-syncopated?

In this post I'll define syncopation more carefully with supporting examples, explain the basic algorithm I wrote to detect syncopations in a rhythmic sequence, and explain why it's important that basically any rhythmic pattern has more syncopated variants than not. What is Syncopation: inverting the hierarchy of beats In music, the passage of time is organized into beats. Or really, it might be more accurate to say, as humans, we naturally and inevitably organize musical events into beats. Repetitive cycles of beats set up a perceptual hierarchy where some beats are "strong" and some beats are "weak." Syncopation, loosely defined, is when a musical event in one manner or another inverts that perception, placing an emphasis on the weak beat over the strong one. This post got kind of long. tl;dr executive summary: 1. Classical music's racism is tied up in its over-reliance and devotion to the past. You can't change one without first changing the other. 2. Various factors subtly reinforce that reliance, especially from the recording era (1920's) onward. One is the plummeting incentive from that time on to write down music note-by-note. The other is the false choice in classical music between the comfortable past and a disorienting, avant-garde present. 3. As such, changing the culture requires much more than just playing more music by black composers. 4. In education, we teachers need to think outside the box in terms of how we teach and what music we teach, which ideally should include guidance and help from our institutions. It’s time we admitted it: classical music is racist. It’s not good for the music, for the culture, or for the people who are pushed away as a result. In this post, I’ll explore how classical music got to this point, why it matters, and what institutions and individuals can do to make it better. This is by no means meant to be exhaustive or comprehensive, but perhaps the start of an overdue conversation. Just a word about me, for those who don’t know me or where I’m coming from. I’m certainly not the final authority here; I’m a white male who’s benefited hugely from the institutions set up that vaguely fall under the “classical music” umbrella (schools, jobs, performances, and so on) though I also have a foot out of that world, partly because I like to write and perform other types of music (though a big part of the issue here is what gets to be, or gets to not be, defined as classical music). At any rate, I’ve grown up with, participated in, and seen the overwhelming whiteness around me in my educational, performing, and teaching life as a musician, so I’ve been part of the problem. It’s easy to be cynical about changing the culture in my (kinda-sorta) field, since I don’t hold too much sway over anyone but myself, but that’s also a dodge, so this post is in the spirit of tackling big problems that need collective action. A Culture Overly Devoted to the Past The racism of classical music comes from and is perpetuated by two basic factors. Most of what most people consider to even be “classical music” comes from the distant past when racism in the world was a fact of life. Today, the world of classical music maintains an at best innocent, at worst lazy and pernicious devotion to that past. And even if it is innocent and passive today, leaning so heavily on the past benefits neither the music itself nor the long term health of “concert music” or “art music” as an idea—though it certainly benefits some people and institutions in the field that don’t want to change it. But changing the culture from a tradition of recreating the past to one that’s more in the present is necessary (though perhaps not sufficient) for making it less white, and in any way anti-racist. Now, that’s not to say there’s no overt racism and discrimination in classical music too, and certainly there’s been plenty when you reach back to the recent past. You may recall the scene from the movie “Greenbook” where black pianist Don Shirley laments the inability to get a gig playing his preferred music, the music he’d “been training his whole life to play” (ie, Chopin). (Yes, he loved the past, too, even more than his own music, it seems, somewhat complicating things!) The global pandemic of coronavirus has forced so many musicians out of the concert halls and into our homes. It's been a challenging week, with the prospect of many more to come. In an effort to keep the music playing and stay connected to listeners, I've started releasing a musical selection for each day of the week. I hope it gives you some respite in these challenging times. All music is original except where noted. This week included a Bach Prelude and Fugue, three pieces for piano and a new song podcast premiere!

Apple podcasts link Spotify link Direct links: 3.1: "Skip" - Baroque / ragtime prelude 3.2: Chorale Toccata 3.3 Meditation #3: Seeking a Higher Power 3.4 Bach Prelude and Fugue in D major 3.5 "Social Distancing:" a song inspired by our new social reality Last year I wrote 25 piano pieces!

-Five pieces for the Left Hand Alone -Schumannia (five pieces) -Syncopated Suite (six pieces) -Two new pieces on the "Mary Had a Little Lamb" theme -Two waltzes ("Ghostly" + "Wheels on the Bus") -Prelude and Fugue in B-flat minor -A musical parody of a Very Bad Piece -Blues, #2 -Ragtime Toccata -Chorale Toccata/Etude See the ones I ended up playing in this playlist here: https://www.facebook.com/sampostpiano/playlist/2954451864619539/ The "Ghostly" Waltz and #1 for the Left Hand were 1st and 2nd place winners in this competition where the participants select the winners, and the Chorale Toccata and Ragtime Toccata were finalists to boot! https://concursodecomposicionparapianofidelio.com/ganadores-ediciones-anteriores/

Note: all musical examples in this post can be played back by opening the page here.

Motivation: Rhythm gets short shrift! Lately, I've been thinking a lot about rhythm! In a traditional study of music theory, one learns a ton about harmony but very little about rhythm beyond some very basics. Similarly, in studying music history, there's an overemphasis on the harmonic trajectory of Western music, but almost no attention to its rhythmic evolution. And yet often the most salient difference between musical styles is rhythmic. Especially when one considers folk and popular music of the past century, there's a surprising continuity of harmony! Rhythm, however, is another matter. The point: Math is useful (and fun!) for building on intuition about rhythm and syncopation This post and the next approach rhythm from a mathematical standpoint, starting with an example of a piece I wrote recently in comparison to one of Bach. In using variations of the main rhythmic theme, I realized most of them were syncopated; this post explains some of the math that backs up that intuitive realization, compares the theme to its obvious Bach counterpart, and motivates further exploration of the topic. The details: Here's the new piece:

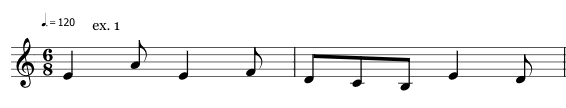

Here's the main theme at the beginning (ex. 1):

Here's the fifth of the recently-completed six-movement "Syncopated Suite"! It starts out like a Gavotte from a Bach suite, but the rhythmic style again evolves into something different! More about this suite coming soon!

It's another "Mary Had a Little Lamb." Don't be fooled by the opening; the piece evolves gradually (and I hope seamlessly) in rhythmic style as it progresses, adding more and more syncopation.

Starts with ragtime-style rhythms but turns into something else entirely. Much of the piece is based on conflicting (between the hands), and ever-changing rhythmic cycles that create not only syncopations but other similarly unpredictable rhythmic accents. The whole piece coming soon...

|

The Music PostThe Music Post is a blog / podcast for reflecting on all things musical, informed by years of writing, playing, and teaching music. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

|