|

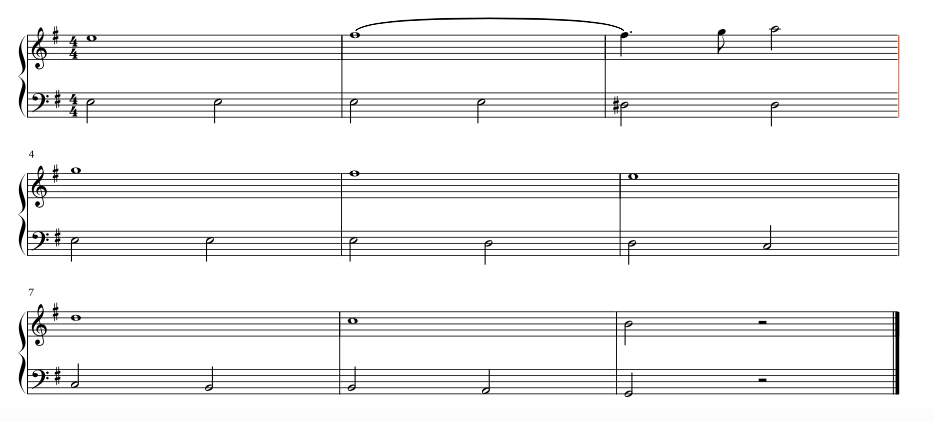

Note: This is the first in a series of practical posts for student pianists and piano teachers. I hope you'll find it interesting as a general music aficionado, but unlike most posts on this page it's not geared toward the listener, and you might therefore find it a bit dry unless you play the piano! One of the principal tasks of the pianist is to clearly show and make as clear as possible the different layers in a piece of music. Here is a basic example from Chopin's Nocturne, op. 9/2 In this case it's important to clearly show the bass line separately from the chords played in the left hand, and the melody separately as well from the two left hand parts, like this: Before getting deeper into detail there, let me point out that on the one hand this task is obvious more generally: music is made not just of a series of notes progressing through time, but of abstractions such as harmonies, melodies, rhythms, and different "voices." The same approach applies to a book or a story: to properly understand the story and make sense of it, it's not enough to know only the literal words of the story; you have to be familiar with the plot, the characters, and the themes of the story. A piece of music is no different. And yet, in practicing, most student pianists never learn to clearly identify, separate, and then separately practice the different layers in a piece of music. Back to the Chopin then, one would want to practice by itself the bass line a few times before practicing the bass line and the melody in combination, without the chords in the left hand: One could also practice the left hand by itself, or the left hand with two hands like this to get a better conceptual separation of the bass and the chords: Why is this sort of practice so helpful? Because hearing three (or even two) layers simultaneously, while playing all kinds of notes, is difficult for everyone. Most advancing students can make a nicely shaped line out of the left hand bass line by playing either of the examples above, but won't be capable, at least initially, of doing so while also navigating to all the chords and focusing on the right hand melody at the same time. By separating the bass line, students get in the habit of listening to it as its own entity, separate from the melody and the other parts, and then as a teacher one can challenge them to add back in everything but keep the same clarity and shape to the parts that was present when focusing on just one or two parts separately. Even just playing the chords on the second 8th note of each group or the third 8th note of each group will clarify the different lines in the chords. (It's these subtle inner lines, by the way, that really make the piece special!) Here would be the third chord of each group, "collapsed" vertically with the bass. Another advantage of practicing this way is that a student will "discover" more easily for him or herself provocative moments that would otherwise be easily glossed over; like the dissonant D on the fourth beat of the first measure in the bass, or the dissonant f-e natural on the third beat of the next measure. My experience teaching tells me that for most students, all three of the above tasks are necessary (identify, separate, practice separately), but that most students are skipping the last one, if not all three! For instance, I often teach performance classes to students who are not my own. Typically, students play from memory, and I often test their memory (apologetically!) by asking them (for instance, in the Chopin example) to play the right hand melody with only the bass line and no left hand chords, as suggested above. Of course, once you know the entire piece by memory, this should be easier than playing all the notes, since it's merely a subset of the notes. But most students are extremely over-reliant on muscle memory in learning their music. Muscle memory is good, of course, but it has to be a complement to aural memory, not a complete substitute for it! If a the student has a clear aural image of the simple bass line, this task is not so difficult. But most of the time, students protest that they can only play all the notes in a piece by memory. To which I gently point out that it's like knowing a story when one can't answer any questions about the story, but only recite it word for word. Let's look at one more example where some of the important abstractions are trickier to identify: Bach's E minor Prelude from Book 1 of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Like in the Chopin, three "parts" or "voices" are notated clearly: the left hand 16th notes, the right hand melody, and the chords in the right hand on every first and third beat. Definitely, a student playing this piece should practice the three parts separately and in all three pairwise combinations. Here are some other important things to recognize (they're not just the purview of the music theorist, they're really important!). First, the left hand really consists of two different voices, the bass note on every first and third beat as well as the 16th notes moving in between the beats. Next, though the melody is beautifully improvisatory, it has an important linear outline motion to it as well when we look at every downbeat note, particularly starting in measure 4 (G > F# > E > D > C > B). When you combine the melody downbeats then with the left hand bass notes, an important dissonance/resolution sequence emerges starting in measure 5, one that's on the one hand frighteningly simple, but easy to miss if you're not looking out for layers. That is, the downbeat of each measure is a dissonant ninth that the bass resolves in the middle of the measure by moving down a step. It is, definitely, a good "summary" of the "plot" of the beginning of this prelude, one that anyone playing should recognize and know intimately! In conclusion let me emphasize once more that the important practice here is not really technical, but rather it is listening practice, which is essentially technique for the ear. Happy practicing!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The Music PostThe Music Post is a blog / podcast for reflecting on all things musical, informed by years of writing, playing, and teaching music. Archives

September 2022

Categories

All

|